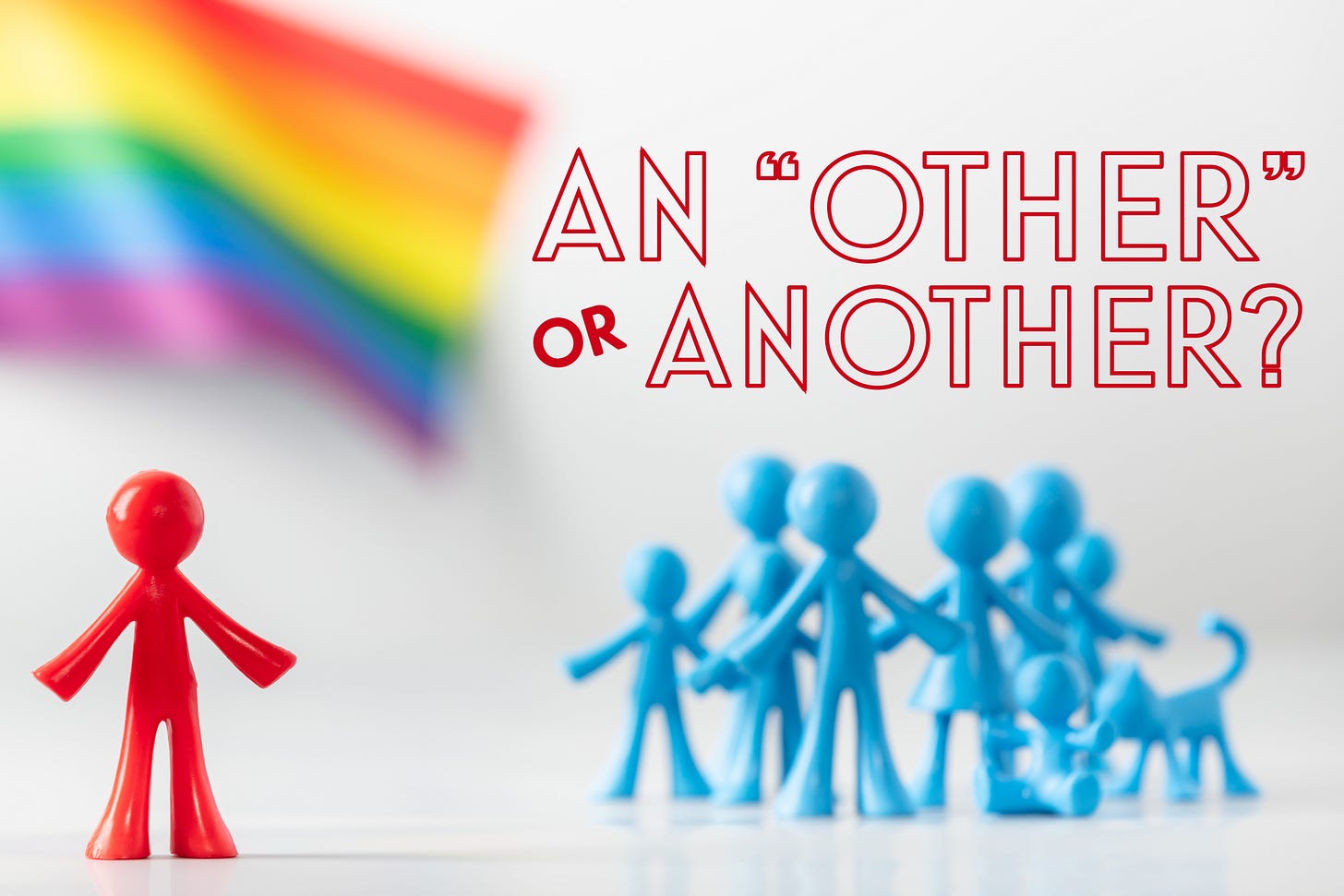

An "other" or another?

As a thirteen-year-old girl in the ‘90’s, I thought I was so cool for having a shiny blue diary with suns and moons on the cover. It even had a lock on the side that used a tiny key! Of course, I had no idea what to actually write in it; it would still be years before I started writing for myself on a regular basis. The pages were mostly blank as the diary collected dust on my nightstand. It did not matter, though; I still felt incredibly sophisticated simply for having it in the first place.

One night, long after my parents went to bed, I hovered my sparkly gel pen (because the diary, of course, required only the best) over one of the light blue pages in the diary. I held the pen there for a moment or two as my heart raced. Writing down “The Big Question” that had been haunting me for months would suddenly make it real. It meant that “The Big Question” would go from something that was just in my head as an amorphous “thing” to something that I would need to address and figure out. Once I wrote down “The Big Question,” it would be out in the world, or at least outside of my head.

I took a deep breath, and in my awkward teenage scrawl, I wrote in big letters, “Am I bisexual?” I phrased “The Big Question” that way because it felt inherently ‘safer’ than asking myself, “Am I gay?” Shame immediately washed over me as the words stared back at me. I wanted nothing more than to take it all back, so that is exactly what I did. I locked the question back in the proverbial closet of my mind, just as I physically locked the diary. Writing “Am I bisexual?” in my diary that night became one of what a college history professor would later call a “watershed moment.” It caused my life – my identity – to change course and go in a different direction than from which it began.

In elementary school, I remember feeling dramatically different from those around me, especially my peers. It is only natural that every child searches for belonging; it is human nature. It felt like more than a simple longing for me. It was a primal need deep in my soul. I knew that I, for whatever reason, inherently did not fit in. Something was different and wrong about me that separated me from my peers. Even though I tried desperately to hide whatever it was about me, I could tell it was visible. My mom has said since I was little that I “marched to the beat of my own drum.” As most mothers do, I know she meant it as a compliment, but it stung (and still stings) nonetheless. It was further confirmation of what I already knew to be true. The feeling of being an outsider was a familiar and constant companion, but I did not have the vocabulary to explain it for a long time.

I understand now, after studying various queer identity development theories in graduate school, that I was far from alone in my experiences. If anything, they were right on par with the theories. Research studies have shown, on average, that it is around the age of twelve when queer individuals recognize for themselves that they are not straight. Those who identify as queer when they are older often express that they felt “different” from their peers when they are in elementary school, but, like me, they were not able to quite describe what it means. Because the cultural perception and acceptance of queer identities is evolving at a faster pace than research, the root cause remains a bit murky. However, it makes sense that we more firmly establish our personal likes and dislikes in elementary school. Recognizing that our likes and dislikes are not the same as others in our age group – even without understanding why – only amplifies the feelings of being an outsider.

I knew for myself at thirteen that I was queer (or, at least that I was not straight), but it was another eight years before I told anyone else. I tried so hard over the course of those eight years to just be another teenager in the crowd. I failed – pretty spectacularly, actually – at hiding my secret and fitting in with my peers as just another member of the group. Puberty is not kind to anyone, yes, but it was particularly cruel to me. I grew early and fast, and I started my period at the early age of ten. At one point, I did not even know I needed to use conditioner (!) on my mess of long curly hair, let alone know how to care for the curls properly. I had a mouthful of braces, thick eyeglasses, and acne scattered across my face (which that can go away anytime now, kthanks.) For some reason, I was strangely obsessed with aliens. Between allergies and the unfortunate luck of catching every cold imaginable, I was always congested and somewhat snotty. In a society of The Plastics, I was a “Desperate Wannabe.” I was a Daria in the world of her sister Quinn. In a school full of Heathers, Veronicas, and JDs, I was a Martha. Bless my little queer heart for trying. She was not fooling anyone.

These days, I easily answer “The Big Question” with a resounding “YES!” However, I do, on occasion, still feel like an “other.” Being the only single person, fat person, queer person, she/they person, etc. in a group means that sometimes, I remain an “other.” It stings far less than it used to because I have a wonderfully strong and diverse group of people in my corner. They take me in as another person without expecting me to change. Trevor Noah, who is as much of a Harry Potter nerd as I am, described friendships as our real life horcruxes because we give bits of ourselves to our friends to hold on to for us, and it is one of my favorite ways to think about friendships. I love the idea that I have people in my life I can trust with various parts of myself, and I am honored to do the same for them. As I have lived in four states over the course of the last twelve years (after undergrad and grad school), many of the friends who “fill my cup” are spread across the country. It takes intentional work and effort on everyone’s part to maintain these friendships, and it is worth every bit.

A few years ago, at the height of quarantine, “Another Big Question” began haunting my brain in the same way that “The Big Question” did when I was younger. Just as I did all those years ago, I opened my journal late one night. I learned from “The Big Question” that writing down “Another Big Question” would be equal parts therapeutic and terrifying.

I hesitated for a moment before putting my pen on the paper and writing, “Do I want to be someone’s mom?” Unlike when I wrote down “The Big Question,” I knew the answer – as scary as it is -- right away.

I have not talked about “Another Big Question” with very many friends, but I have been quietly working towards my answer for the last two years. I am surrounded by so many loving and beautiful families, and while my family will be filled with just as much (if not more) love as the other families, it will not look like them. As a queer person in my late thirties, conception is not going to happen naturally. I mean, it could, technically, but trust me, that is not an option. I am also preparing to be a single parent by choice.

My intended path is neither conventional nor common. It should not surprise anyone, but in a heteronormative society that prioritizes partnerships, it is hard to find another queer person in their thirties who is going through (or will be going through) fertility treatments to be a single parent. I was just getting used to feeling like an “other” when I reconnected with a friend. Her story is very similar to mine, with one exception: she is expecting twins in the spring. While our paths are still very much our own, I no longer feel like I am an “other” because, simply put, she gets it. Reconnecting with her reminded me that while I may feel like an “other,” there are other “others” out there too.

I am not as nearly alone as I feel, which is reassuring. While being an “other” never happens in a comfortable place, I can make the space more welcoming for the other “others” who are on their way. I am determined now to hold the door open until another “other” arrives and I can welcome them inside.